Do you believe in the power of building a happy workplace to grow your business? We definitely do, and this week we bring proof. This week’s guest is an expert in creating joy at work, no matter how many days a week you’re in the office. If you need some inspiration to build trust in your team and set the foundations for a happy culture, this is a must-listen for you.

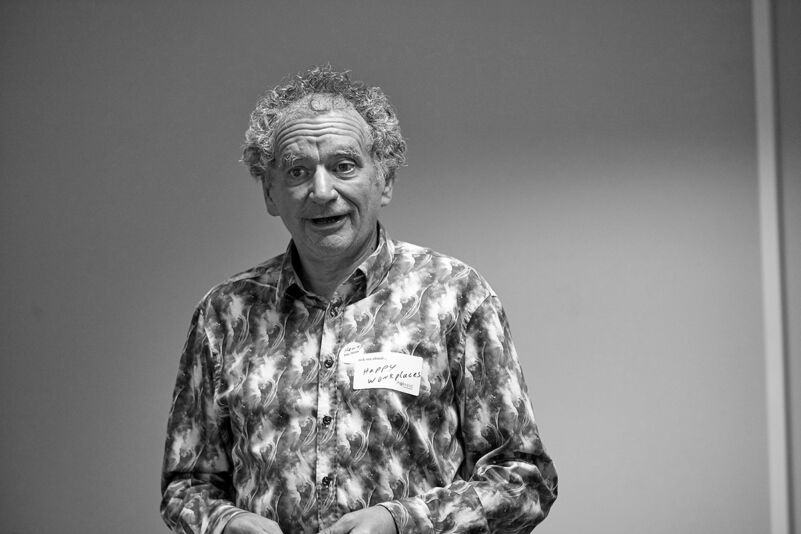

This week on Curious Leadership, we learned from a long-time friend, Henry Stewart, founder and Chief Happiness Officer of Happy, a company that helps organisations create happy workplaces. Henry and Dominic met many years ago when their organisations were competing for the Unisys Service Excellence Awards. Happy is the second happiest company in the UK or Best Place to Work, as measured by the Great Places to Work organisation, and number 15 in Europe.

Henry has an innovative approach to running a business and was part of the British pilot for four-day work weeks. Then, he decided to continue on that path, which resulted in 40% year-over-year revenue growth and increased productivity. He also implemented a salary transparency system, made the staff set his salary, and decided not to make any decisions, after which his employees took ownership of raising prices during the pandemic, which ultimately saved the company. Henry is now exploring Employee Ownership Trust and is happily living out his 4-day work week.

Download and listen to this fantastic conversation today.

On today’s podcast:

- The impact of a four-day week at Happy

- Implementing salary transparency in Happy

- Should your staff decide your salary?

- How to maintain productivity with a four-day week

- Can a CEO make no decisions?

Follow Henry Stewart:

How to lead a great place to work and create a happy culture?

Henry Stewart is the founder, and Chief Happiness Officer of London-based learning provider Happy Ltd. Happy was rated one of the top 2 workplaces in the UK in 2022, and one of the top 15 in Europe (in the SME section). It now helps other organisations create happy workplaces.

Henry was listed in the Guru Radar of the Thinkers 50 list of the most influential business thinkers in the world.

Happy started off as IT software training, enabling people to enjoy their software, which is still about a quarter of the business. So if you want to learn about Excel, come to Happy, says Henry. With a training centre in Oldgate, the pandemic made them wonder if they would continue to use it. After two years vacant, and a big debate, they decided that even if there was one room available a day, it would be worth keeping.

“We deliver learning, and a lot of people still want it in the classroom at the moment. So obviously in the pandemic, it was 100% online, but now it’s 50-50 classroom online. So people want to come back to the classroom.”

Today, Happy also helps organisations create happy, productive workplaces that are far more effective than they were before. Their clients are looking to improve the wellbeing of their staff, whilst also focusing on getting a strong economic impact.

Henry shares the example of Macquarie Telecom that, after working with Happy in creating a happy workplace, saw a threefold increase in its share price, and it has more recently seen a tenfold increase. Another example is Sarah Pew from Heart of Kent Hospice, who went from 350 clients to 900 clients without any increase in staff. Based on putting in place the ideas of the Happy workplace.

Working from Home vs back to the office

Henry admits that he doesn’t worry about where people do their work. At the moment, they have about three or four people still in the office.

“I suppose the point about the classroom is that people get together, they meet, they engage, they discuss, and for a lot of people, they really like that. Obviously, online is great if you’re remote, if you’re across many countries or things like that. But often people like the classroom.”

At the end of their course, Happy conducts a survey asking whether they prefer online or classroom. During the pandemic, 60% of the learners preferred online, whereas now that people are back in the classroom, 95% prefer the classroom.

There’s a fundamental human truth about coming together to do great work. If you work for an average company, perhaps people wouldn’t want to commute to do a dull job with not very good colleagues. The average is always different from the top five or top 10% of companies in the world. But, for Henry, you don’t need to have everybody in the office to be in the top 10%. In fact, Happy is in the top two best workplaces in the UK at the moment and the top 15 in Europe.

“I like to think we are in that top 5% and somehow we work, somehow people are engaged even though some of them are not in the office. We’ve had one person, our marketing manager hasn’t been in the office for three years, and she does a very fine job and manages to engage with other people.”

Maintaining productivity with a four-day week

Before Happy joined the UK pilot to try the four-day week, they surveyed the team. The majority wanted to do it, and they were really keen to be as productive as before.

“And one of the interesting things in the survey that we did was that 77% are literally working just for 32 hours and the other 23% are working one or two hours over. And beforehand they say that I actually used to work over hours.”

Some people could argue that people could be more stressed in a four-day week. But Henry says that actually, their survey shows people’s wellbeing has improved. And he adds that according to an article in the Economist published a few years ago, people in the UK are only really focused for two and a half hours a day. In Canada, it’s only one and a half hours.

The key point about the four-day week, says Henry, is that you get 100% of your salary for 80% of your time as long as you are 100% as productive. That’s why 70 organisations joined the pilot, to see if their teams could be 100% as productive in four days. Virtually every pilot company continued with the four-day week because they were as productive.

But how do they measure productivity?

“The key measure for us is, are we 100% as productive in terms of customer feedback and in terms of income? That’s the key question. And we actually grew by 40% last year without any increase in staff, and we’re expecting to grow another 10% this year. And that for me says that we are as productive as we were before because we’ll get as much done in less time.”

And that is a win-win. It’s a win for the employees that get the day off, and a win for employers because we get things to be much more productive. According to Henry, every single company that joined the pilot has achieved the same level of productivity in four days as five days. And none of them has gone back to the five-day week.

Actionable ideas to improve productivity

One of the key things that have helped increase productivity is cutting back on meetings. There are either fewer or shorter meetings. Also, people use the day off to focus on their personal stuff, rather than doing it on work days, so people are much more focused. Interestingly, Henry has run a Productivity Blitz course for years and no one at Happy was interested in attending until they rolled out the four-day week.

“When they did the four-day week, they all wanted to be on it. And as a result, people are really focused, just to be honest, most people get lots of email alerts, slack alerts, and lots of Teams alerts, and they don’t actually get much done, right? So the key is to really be focused in your time, stop the email alert, stop the teams, and instead really get deep work done.”

It’s also about time management, for which you can make use of some great tools like Pomodoro, which time you with 25 minutes of absolute focus, followed by 5 minutes break. Another tool Henry mentions is Eat the Frog, instead of a to-do list, at the end of the day you write down the four most important tasks you have to do the next day first thing in the morning.

What Henry does and what he encourages everyone at Happy to do is check emails three times a day. That is to cut off the alerts, check email three times a day and take 21 minutes and reduce it to zero.

“Sometimes your email is a task like ‘write a business plan’ or ‘do this project’, and that then goes into tasks, and you’ve set some time for that, but everything else you delete it, do it, or delegate it.”

Salary transparency and deciding CEO’s salary

Some time ago, Henry published an article saying that his staff was setting his salary. This publication caused a wave of emails from CEOs that believed Henry was insane.

Henry defends the idea that it’s his staff that knows best how valuable he is. The board doesn’t know it. The shareholders don’t know it. And for that reason, it’s the staff who know what his salary should be worth, he argues.

“Two years ago, I decided to let staff set my salary. And oddly, it’s not gone viral. I mean, the idea of setting salary isn’t going viral. The blog went viral. Oddly, nobody else seems to want to do it.”

His team decided to pay Henry above the salary band he was expecting. This, he says, makes him feel really valued. It’s a move that not everyone gets, and that might not work for every CEO, but works for him.

Ever since they read Maverick by Ricardo Semler – around 30 years ago – Happy has had transparent salaries. And every time they conduct their yearly survey about it, at least 85% of people say they like having salary transparency.

“We have a spreadsheet which shows every salary everybody has earned right back to when they started, plus the three reasons why they got that salary increase. And why wouldn’t you want people to know why people get a salary increase? You don’t want people to say, oh, it’s because he went down the pub with Fred or whatever. You want them to know what it is that creates an increased salary in your organisation.”

Can a CEO make no decisions?

Another thing that Henry has decided to do, along with letting his staff decide his salary, and continue with the four-day week is to make no decisions. Henry tells us about the time he was in a panel with David Marquet, author of Turn the ship around, and previous guest on the podcast.

David was the commander of the US. Navy submarine, and he didn’t know how it worked. He’d been trained for another submarine, and so he decided that, instead of him dictating to 125 crewmen, he would have them decide how to do things, and he would coach them.

“So, when the managing director of our IT business moved on, I decided to stop making decisions. And it was brilliant. As a result of it we grew by 25% a year in the next couple of years, and we were going to be growing by 25% in the pandemic, but we lost 95% into our business at that point. And what happened was people took real accountability and real responsibility.”

Henry also confesses that when he read the Happy Manifesto ten years ago, he thought they had a trust-based environment at Happy. But when he stopped making decisions, he realised they didn’t. People were still relying on him, but since he’d stopped making those decisions, they started taking their own responsibility.

To illustrate, Henry shares the example of Ben and John, who were looking at their pricing and realised it didn’t reflect today’s market. This wasn’t their responsibility, but they decided to take it on. They talked to loads of people, looked at the market and their competitors, and then they talked to Henry to propose a price increase.

“I wasn’t that keen on it, but they said they went ahead with it because it wasn’t my decision. And what I reckon now is that they were far more effective in deciding that price rise than I would ever have been, because I’m based on kind of 20, 30 years ago what prices were then. They are based on what it’s like now. They know the clients, they know what’s going on. And so that price rise probably enabled us to continue through the pandemic.”

Keeping the values with an Employee Ownership Trust

Henry is now contemplating selling the organisation to its employees, but he doesn’t see that as his exit strategy. He’s only 63 and has a lot of time left.

“I love working for Happy, and I love the fact I don’t need to make any decisions, and everyone else does that because I don’t micromanage, I’m not stressed at night. So the Employee Ownership Trust is a fantastic idea because I’ve had various people come to me and say, we want to invest in your business, we want to take over your business, but none of them has the right values. So the point of the Employee Ownership Trust is, of course, it will keep the values because it will keep the staff.”

Also, for an outside investor, that’s a big sale point because you set the evaluation for the organisation. In Happy’s case, it’s based on three times that year’s profits, two times the year before and one time the year before that. So they will sell the company, and also have share options for staff.

“So when we put in place the idea of the Employee ownership Trust, we also put in place share options for staff so that they will also benefit from the results of this. And so we’ll send it to Employee Ownership Trust, which is like the John Lewis model, and then the staff will own it. And one of the great things about that is the profit-related pay bonus is tax-free up to three and a half thousand pounds.”

Book recommendations

Reinventing Organizations by Frederic Laloux