This week we learned from the inventor of the Outcome-Driven-Innovation (ODI) process, Tony Ulwick. Tony developed this process and, in 1999, he described it to Clayton Christensen, author of The Innovator’s Dilemma. Although Clayton loved it, he didn’t like the idea of customers having a process, so he called it Jobs-To-Be-Done. Every customer has a job to be done, so what we can do is innovate around solutions to help them get that job done.

What’s the job your customer is trying to get done? And how do you measure success? In this episode, Tony guides us through the process that innovators need to answer those questions, and he shares some interesting case studies of how he’s helped different firms understand what jobs their customers were trying to get done, and how to identify their unmet needs.

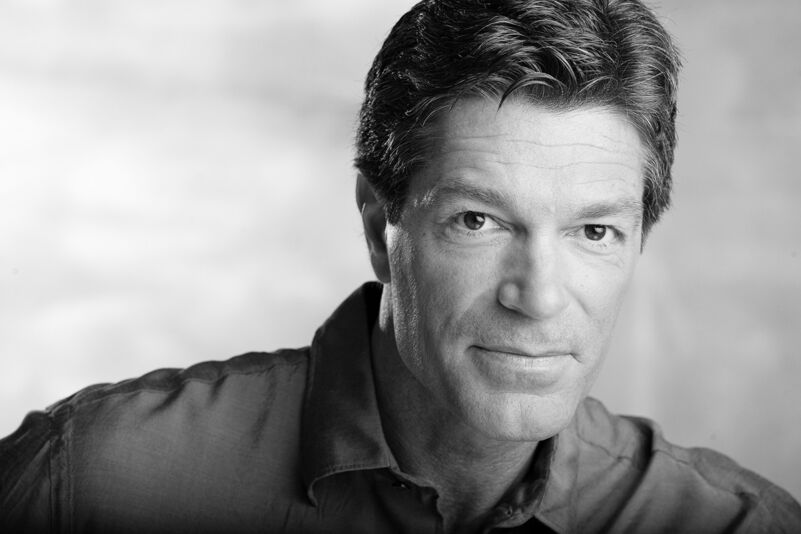

A fascinating conversation with Tony.

Download and listen to learn more.

On today’s podcast:

- The Jobs-To-Be-Done Theory

- How can you define a need

- The cases of Bosch and Conagra

- How your customers measure success

- Understanding the job that your customer is trying to get done

Follow Tony Ulwick:

Jobs To Be Done – Book and Audiobok

How To Measure Customer Success with Tony Ulwick

Tony Ulwick is the pioneer of the Jobs-to-be-Done Theory, the inventor of the Outcome-Driven Innovation® (ODI) process, and the founder of strategy and innovation consulting firm Strategyn. He has applied his ODI process at some of the world’s leading companies and across nearly all industries to inform breakthrough innovations—achieving a success rate that is 5 times better than the industry average. Philip Kotler calls Tony “the Deming of innovation” and credits him with bringing predictability to innovation. Published in Harvard Business Review and MIT Sloan Management Review, Tony is also the author of best sellers What Customers Want and JOBS TO BE DONE: Theory to Practice.

Tony has been in the innovation space for more than thirty years. His career started at IBM, and then he founded the consulting firm Strategyn in 1991, where he is also the CEO.

Jobs-To-Be-Done Theory

Although he came up with the idea of the Jobs-To-Be-Done concept, Tony admits he wasn’t the one that gave it that name. He first introduced what he called the Outcome-Driven Innovation process to Clayton Christensen, author of The Innovator’s Dilemma, back in 1999. He explained to Clayton that we have two ways in which we can look at a market: through the lens of the drill maker, or through the lens of the hole maker.

“The beauty of looking at a market through the lens of the hole-maker is that you can study a process because now you’re studying what the customer is trying to accomplish. You’re not asking customers about products, you’re not asking them how to make a better drill. You’re asking them all the steps they go through and how they measure success as they try to create the quarter-inch hole.”

Clayton was fascinated by this idea, tells Tony, because what they did was make the underlying process the unit of analysis, which brought a whole new set of insights to the innovation process. However, Clayton didn’t want to say people buy products to get a process done. Instead, he said they buy products to get a job done. He introduced the concept in 2002 in his book The Innovator Solution.

How to define a need

Tony says that people believe customers don’t know what they want. But, often what happens is that people don’t know what solutions they want. Innovators often combine solutions with needs. They use these two terms interchangeably. But, of course, he adds, a solution satisfies a need, which means we first need to define what a need is.

“The way we define a need is those metrics that people use to measure success as they go about and get a job done. So as you’re preparing a meal, you want to minimise the time it takes to prep the food. You want to minimise the likelihood of overcooking, minimise the likelihood of undercooking very specific measurable outcomes that you’re trying to achieve to get the job done.”

People buy products that get jobs done. So, studying the market through that lens gives innovators a great advantage. A lot of people don’t think innovation is a process. And many of those that do, think about innovation as a process of coming up with solutions that address unmet needs. But the way they go about doing it is they start with the solutions. They come up with hundred ideas and then check whether the customers like them hoping they’ll satisfy their unmet needs. And the reason they do that way is because they don’t know how to define all the unmet needs.

“First figure out which are unmet, and then just devise a single solution that addresses the top unmet needs. That would be ideal. And that’s what outcome-driven innovation allows you to do. But it forces you to think about what a need is very differently.”

Tony explains that on product teams, over 80% of them don’t agree on the best way to define a market. They don’t define it as a group of people getting a job done. They define a market as a product or a technology or a vertical or a use case or something else. And over 90% of product teams don’t agree on what a customer need even is. Is it a specification, a requirement? A pain, a gain? An exciter delighter? A value driver?

People continue to struggle to innovate because they can’t grasp the concept of what a need should be, and that’s why they experiment instead. They don’t think it’s possible to know all the needs, prioritise them and then figure out which are unmet before coming up with the ideas, says Tony.

Clayton Christensen’s milkshake story

Clayton Christensen uses the story of a fast-food restaurant trying to sell more milkshakes to exemplify how the jobs-to-be-done theory works. The first attempts of the company to increase the milkshake sales had failed, so they asked one of Christensen’s fellow researchers for help. After spending some time in one of the chain’s restaurants, they discovered that 40% of the milkshakes were bought early in the morning, by commuters that ordered them to take away. When asked what job they ‘had hired the milkshake to do’, it turned out that they usually had a very long and boring commute ahead and they just needed something to do whilst driving. They needed something to keep busy.

Tony argues that this story, although entertaining, is misleading because most of what Jobs-To-Be-Done is about is coming up with the right product concept, not by studying the product, but by studying the customer’s job to be done.

“Clayton starts with the notion that I want to sell more milkshakes. Well, if you want to sell more milkshakes, that’s a different problem than saying, I want to create a product that really gets the job done really well. And that job is to get breakfast on the go. He started with the product in mind, as opposed to the underlying job that the customer is trying to get done.”

The Conagra case

One of the companies that Tony has done some research on is the American Consumer Packaged Food holding company, Conagra. They make breakfast products. So, Tony studied the job of consumers, commuters who are in their vehicles trying to get breakfast on the go. And when you start breaking down that entire job, he adds, you can see where a milkshake might be a good solution, but you could also come up with other solutions that get the job done better.

“In fact, a lot of the innovations in getting the job done had nothing to do with the food product. It actually had to do with the service in terms of making sure you could prep it very quickly, because people only have like six, seven minutes. They’re allocating to get their food. And if it’s unpredictable in some morning, it takes ten minutes or twelve minutes.”

The innovation was about making sure that the processes are set in place so that the expectations of receiving the food are consistently met. So, they could plan it was going to be six minutes, and they’re not going to be late for work.

At Conagra, they struggled to come up with a potato-based product that would get the job done better, because the opportunity wasn’t necessarily with what they were eating. It was with all these other aspects of getting the job done. So they experimented with a few things and eventually gave up on the concept of creating a breakfast food that would satisfy the top of their outcomes because they felt like a potato product couldn’t satisfy those needs, says Tony.

“They knew that they couldn’t create a product that got the job done better, because the job is much bigger than just eating the piece of food. The job is going to the location, getting in line, ordering the food, making sure the order is taken correctly, waiting for the food, getting your condiments, make sure what you get is what you ordered. All this stuff has to happen before you even open the bag and reach for your food. So you’re studying the entire job the customer is trying to get done, and instead of just the job, the products getting done.”

How to measure success

Most companies don’t know why their customers buy from them. That’s why, for Tony, when you look through the lens of the ‘hole-maker’ the world looks a lot different.

“We’re not defining markets as products or technologies or use cases or verticals. We’re defining a market as a group of people and the job they’re trying to get done. When we talk about customer needs, we’re not talking about pains, gains, excited delighters, requirements, specifications, value drivers, benefits, and features. What we’re talking about are the metrics people use to measure success when getting a job done.”

Tony argues that you can break down the job your customer is trying to execute to understand how they measure success. For example, he works with a lot of B2B businesses, and surgeons and studies complex processes. Often, they come up with over a hundred statements of what success looks like. Then, they use them to survey customers and ask them how important each outcome is and their current level of satisfaction with the solutions they use today.

Once they gather the information, they have two data points. From all the dimensions, which ones are the important ones and not well satisfied by the existing products? In other words, you’re figuring out precisely where the market’s underserved, and where we can help customers get the job done better.

“And if you discover a half dozen or a dozen or more unmet needs, then the question is, how do we solve them? Can we solve them? We know the opportunity in the problem space. We’ve just identified it. Can we solve it in the solution space? And that’s the fun part. Once you know what these unmet needs are, can you solve them? And the answer usually is a resounding yes.”

The Bosch Case

To further illustrate this, Tony used the example of Bosch and when he help them enter the North American circular saw market. The circular saw wasn’t new in the North American market, so what Bosch was trying to do was find something that could give them a competitive advantage. So, when they studied the job of cutting a piece of wood in a straight line. What was a simple job had about 72 different outcomes or metrics that people use to measure success, and fourteen of them were underserved in the market.

The inevitable question that the Bosch team asked was ‘which one should we focus on?’. What Tony suggested is to go after all of them.

“The reason I said that is, if you’re trying to enter the market against the wall to Makita – established players– you’re going to have to get the job done a lot better. If you get it done a little better, nobody’s going to care. I love asking this question like, would you switch from your favourite brand or product if another product gets the job done just 1% better? Probably not, maybe not 2% or five. But at about 15% or so you’re going to go, yeah, if it gets the job done that much better, I’ll consider it. And so that’s what we did with Bosch team.”

It took a group of engineers about 3 hours to come up with solutions that addressed all those unmet needs. Once they did, they told Tony that they’d had those ideas before, but the problem was they’d had thousands of ideas before, and didn’t know that those fourteen were the ones that would really matter. So when they were presented with the challenge of solving these problems, they could solve them. They just didn’t know that was the right combination that would get the job done significantly better.

“Bosch knew that that product was going to win because it had that set of features that address those needs that were determined to be unmet through the research by studying this job that the customer is trying to get done. So it brings predictability to the process. So instead of coming up with lots of ideas and hoping some might address some unmet needs, we’re going to uncover all the unmet needs and then surgically ideate around those needs to come up with a solution that addresses them. So you’re securing that product market fit before development even begins.”

What is your customer trying to get done?

In this process, the first thing you have to determine is who your customer is. That is, who is the job executor? That, says Tony, is an important decision to make because you’re trying to create value for a group of people. The second step is to figure out what job they’re trying to get done. When it comes to this step, there are two ways to look at it.

“Companies often already have products, so they go out to customers and say, what job does my product do? That’s okay. You could create a product that gets that job done better, but a better question is to ask, when you’re using that product, what is the job you’re trying to get done?”

For instance, if you’re a kettle maker, you can go to customers and ask them why they are buying your kettle. They could tell you it heats water to the desired temperature. You could study that job and make a great kettle. Or, you could say, what other products are you using in conjunction with that kettle? What job are you trying to get done? In other words, adds Tony, don’t tell me the job you are trying to get done. Tell me what you are trying to get done.

“And as the manufacturer of the kettle, you can go in either direction. You could stay narrow and say, let me just focus on what my product does and do that really well. Or you could go broader and say, well, let me focus on the job the customer is trying to get done because I’m already in that market. And if I focus on it more broadly, that gives me opportunities to grow more into the market.”

When you talk to customers, you’re trying to break down the job they’re trying to get done. You ask them how they measure success along each step of the way, says Tony. Ask people what they are trying to achieve. Time-consuming aspects. What are they trying to avoid? What things go wrong? What makes it unpredictable? What leads to poor results? And if we can get the job done fast and eliminate all the bad things from happening, we’ll get the job done better.