Quick Summary

Every time I see a nine-box talent grid, a little part of me dies. It isn’t science, it’s HR astrology, tarot cards in Excel, built on that bloody word: potential.

Takeaways

- Most companies treat potential as mystical fortune-telling instead of evidence from real behaviour.

- Great individual contributors are often pushed into management they’re not suited for.

- Nine-box grids blur performance, values, and courage, and let leaders dodge hard decisions.

- Real potential shows up in people who raise standards, take ownership, and step into leadership before they’re given the title.

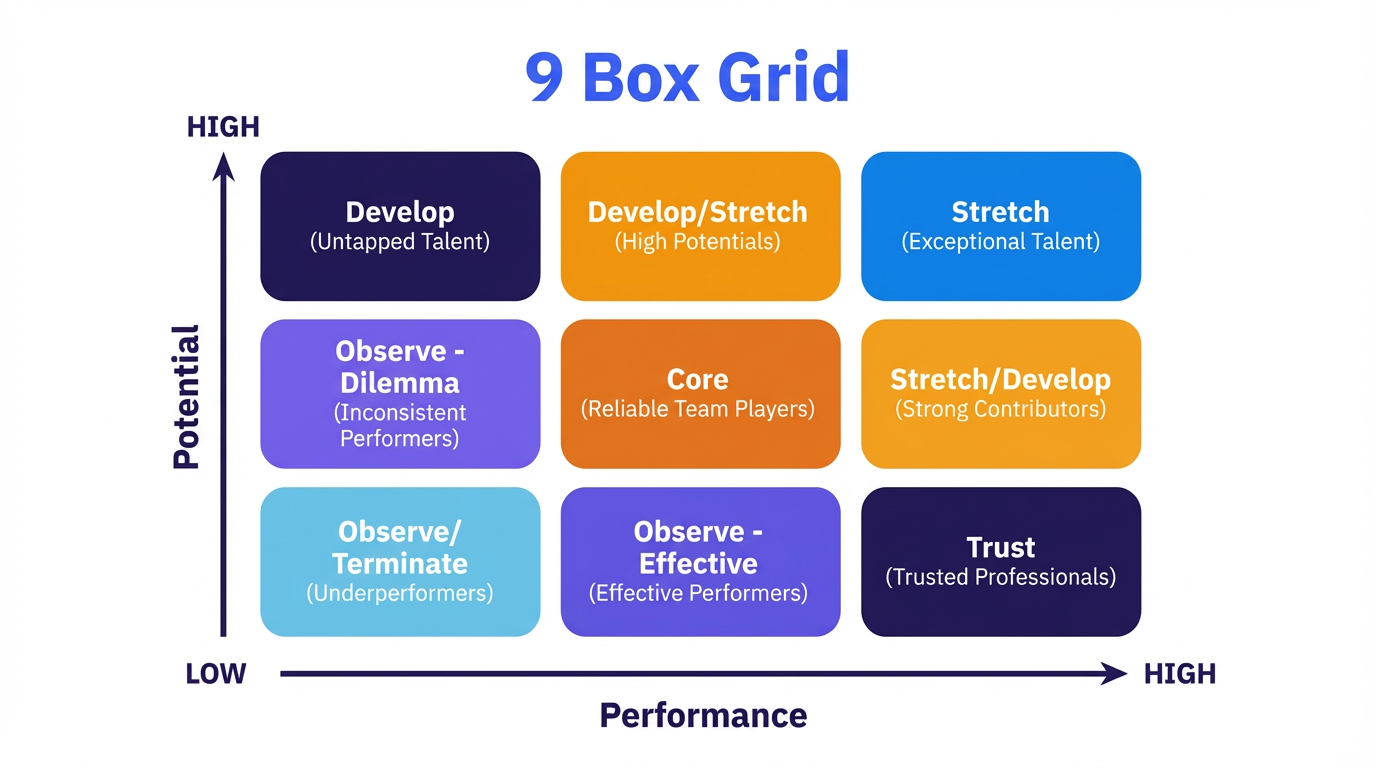

Every time I see a nine-box talent grid, a little part of me dies. You know the one I mean. Performance on one axis, “potential” on the other, lots of coloured squares, HR people getting excited about calibration meetings as if they’re launching a Mars mission. Everyone sits there nodding gravely, pretending this is science.

It isn’t. It’s HR astrology. Tarot cards in Excel.

And the bit that p*sses me off the most? That bloody word: potential.

Potential for what? Compared to who? On what basis? Most of the time, “high potential” just means, “they’re slightly less crap than everyone else in this under-performing team, and I don’t want to upset them, so I’ll put them in the shiny box in the top right.” That’s not a talent strategy. That’s cowardice.

If you’re trying to scale a business, you cannot afford to delude yourself like this. You need people who can do the job now, and a way of spotting who might be able to do a bigger job tomorrow based on evidence, not optimism.

Potential for what, exactly?

The first question hardly anyone asks is the most basic one: what sort of potential are we even talking about?

Inside any growing business there are really two very different ladders. One is the ladder of the individual contributor. That’s the person who gets better and better at their craft. They might move sideways, but fundamentally they’re still a doer.

Then there’s the management and leadership ladder. Team leader, manager, maybe director. Less doing, more thinking and coaching and deciding. You spend more time dealing with people, conflict, trade-offs, ambiguity and pressure. That’s a completely different job.

What most companies do is ignore this difference and stick everyone on one generic “potential” axis. So you get people who are fantastic at their job being pushed into management whether they want it or not.

Being brilliant at your own job does not automatically mean you’ll be any good at managing others. In fact, some of the best individual contributors make sh*te managers. You promote them and all you succeed in doing is breaking first them, and then their team.

Why the nine-box grid is HR astrology

The nine-box sounds clever on paper. Performance versus potential. Put people into coloured squares. Top-right box is the promised land.

But under the surface, it’s a mess.

Performance is shaky enough in most businesses, because hardly anyone has clear, up-to-date scorecards. Potential is almost always a pure guess: a mix of likeability, noise level and length of service. Yet once it’s drawn on a slide, everyone treats it as gospel.

I use a six-box grid with clients: A, B, C for performance, crossed with values fit or not. That’s it. Simple, but actually useful. Either you hit your scorecard and live the values, or you don’t.

Nothing in that grid is about potential, and that’s deliberate. We don’t need an extra axis to speculate about someone’s imagined future. We need to know: are they doing the job now, and do they belong in this culture?

The nine-box tends to become a way of avoiding hard decisions. Instead of saying, “This person is a solid B and we either coach them up or move them on,” you say, “Well, they’re a medium performer but high potential,” and somehow that means you keep them around indefinitely.

A real example of potential (and why teams hate it)

My niece has just joined our organisation for a while, as she’s taking some time out before university. She worked at a hotel in Ireland before coming to us, where she did exactly what every manager claims they want: worked hard, learned quickly, showed enthusiasm and took initiative.

What did they do? They reduced her hours and ostracised her. She was working too hard. She stood out. She was raising the bar – and the team didn’t like it.

She absolutely has potential. That’s what I mean by potential: behaviour and backbone, not a label in a spreadsheet.

But in a lot of organisations, someone like that doesn’t get nurtured. They get frozen out. Because most people would rather protect the comfortable average than be forced to lift their own game. The Stanford experiment on slacking showed this: most people drift down to the level of the lowest performer. The rare ones drag the standard up. And they’re often unpopular as a result.

So when I talk about potential, I’m asking, “Who raises the bar even when it makes everyone else uncomfortable?”

Promotions today, not prophecies for tomorrow

Another problem is that “potential” becomes a way of talking about the future while ignoring the present.

You hear nonsense like, “They’ll be ready in 18 months.”

But if we’ve got a role to fill today, the question isn’t, “Who might be ready in 2027?” It’s, “Who is good enough now?”

You wouldn’t pick your starting XI for a cup final based on who looked good two seasons ago. Nor would you pick it based on players you think will come good two years from now. But that’s exactly what some companies do, because they’ve convinced themselves that “potential” is a fixed property, not something that’s constantly evidenced by current behaviour.

I’m interested in what people are doing now: the decisions they make, the problems they solve, the way they behave under pressure. That tells you far more than any label you slapped on them last year.

How you actually spot management potential

If you want to know who might become a great manager, you don’t rely on a grid. You give people leadership-shaped work before you give them a leadership title or a pay rise.

You deliberately create opportunities that look and feel like leadership: influencing others, co-ordinating activity, owning something that matters, making decisions where there’s no obvious right answer. Then you watch what they do.

Some people step forward, take on the extra responsibility without moaning, and they deliver. They rally others and improve things. Those are your future managers.

Others nod enthusiastically in meetings and then do absolutely bugger all when it’s time to act. They like the idea of being important but not the reality of doing the work.

This is all observable. It’s behaviour, not theory.

Using real work as a leadership lab

Inside scaling businesses, there are endless opportunities to turn real work into a leadership laboratory.

You can set up a charity committee and see who drives it forward. You can hand ownership of facilities or onboarding to frontline teams and see who turns that into something valuable.

At Next Jump, they’ve institutionalised this thinking. There’s someone accountable for recruitment – the captain – who’s now the coach and owner. They also have a designated successor. And they think ahead to the successor’s successor.

These roles run in six-month stints. Your job is to get the work done and to make sure your successor is ready to take over.

Leadership opportunities are created on purpose, rotated frequently, and used to build a deep bench. That’s how you grow management capacity. Not by arguing about who belongs in the top-right box.

Make yourself redundant (twice)

One of the most important mindset shifts for any manager is this: your main job is not to get the work done. Your main job is to make yourself redundant.

If you believe your job is to get the work done, you’ll hoard tasks and decisions. You’ll become the heroic bottleneck who’s always busy and always in the way.

If you believe your job is to make yourself redundant, everything changes. You start looking for successors. You delegate properly. You train people to take over.

So we ask clients, “Who is your successor?” And then, “Who is your successor’s successor?”

If any team leader or manager doesn’t have an answer, they haven’t understood their role. They’re protecting their status, not building a system.

And both successor and successor’s successor need to be A-players. If they aren’t, you haven’t got a succession plan.

Why you don’t need “potential” on the grid

Between the six-box grid we use (performance and values), the discipline of succession, the leadership experiments I’ve described, and decent scorecards, we’ve already solved the real problem.

We can see who should be promoted. We can see who might step into management. We know who needs coaching. We know who needs to leave.

That’s what the nine-box is meant to help you with. It just does a crap job because it blurs everything together and invites people to make things up.

Instead of asking, “Who might be good in the future?”, we ask, “Who is good now, and how do they behave when given the chance to lead?”

The behaviours that matter

When I do think about potential – particularly for management – I think in terms of behaviours I can see. People who learn quickly. People who make decent decisions under pressure and don’t freeze or dump the problem on someone else.

Influence without authority is a big one. If you can’t get anyone to follow you now, giving you a title won’t magically fix that.

Then there’s the effect they have on the team. Do they drag the standard up or drift down? The rare ones drag everyone else upwards. Those are the people you want leading teams.

And finally, I look for values and backbone. Will they make the hard call because it’s the right thing to do? Are they willing to have difficult conversations and hold the line on standards?

That’s the stuff that tells you about potential. Not whether their name sits in a box next to the words “high” and “future”.

Why managers are the worst judges of potential

Most managers are terrible at spotting potential. They’re drawn to people who are easy to manage, loyal, or similar to themselves. They confuse comfort with capability.

A better way is to use a coaching programme. Ask, “Who would like to be a coach?” Then ask the rest of the organisation, “Who would you like to coach you, who isn’t your boss?”

Now you’ve got two signals: people willing to coach, and people trusted by their peers. Overlay those and you get an informal map of where the organisation believes leadership lives.

You suddenly see the quiet influencers, the ones everyone turns to, the people who don’t shout in meetings but who get things done.

The Clive Woodward lesson

I love Clive Woodward’s reflection on England’s Rugby World Cup win in 2003. After a disappointing exit in 1999 at the quarter final stage, he simply refused to have anyone negative in the changing room for the next campaign. He wasn’t demanding perfection. He was saying he wouldn’t tolerate people who dragged the environment down.

That’s a very useful filter. I’m far less interested in whether someone ticks every competency box, and far more interested in the effect they have on the mood, energy and standards of the group.

If you’ve got people who raise the bar, take responsibility and stay positive, they’re worth developing. If you’ve got “high potentials” who are cynical and corrosive, I don’t care what your grid says, you’ve got a problem.

Ditch the tarot, build a pipeline

If you’re a founder CEO trying to scale, you do not need HR tarot cards. You need a pipeline.

You need clear performance expectations and values. You need the courage to admit when someone isn’t cutting it. You need managers who understand their job is to make themselves redundant, twice over. You need visible opportunities for people to step up and lead before they get the badge. And you need to fill vacancies with people who are good enough now.

Do that, and your organisation will tell you who has potential every single day through their actions. You won’t have to guess. You’ll just have to notice – and then have the guts to promote the right people and let go of the wrong ones.

Written by business coach and leadership coaching expert Dominic Monkhouse. You can order your free copy of his new book, Mind Your F**king Business here.