Quick Summary

Buyers don’t buy your deck or your vision. They buy a shortcut so they don’t have to build it themselves.

Takeaways

-

Buyers aren’t buying a “great business”, they’re buying a fast, low-risk solution to problems they don’t want to solve themselves.

-

Being exit-ready means being valuable to a specific buyer, not just busy, polished, or technically impressive.

-

Growth and profit are the entry ticket, not the prize, the prize is a clear strategic reason a buyer would pay a premium.

-

If you don’t know exactly why a buyer would buy you, you’re building potential, not an asset, and potential doesn’t get paid well.

Buyers don’t buy your deck or your vision. They buy a shortcut so they don’t have to build it themselves.

So many founders prep for exit like they’re staging their house for sale. They make sure the front rooms all look amazing, and hide decades-worth of crap in the loft and hope no-one looks there. KPIs are tweaked to perfection, numbers are massaged beyond all recognition, and speeches and presentations are rehearsed to within an inch of their lives.

And then, the chaos hits. A buyer turns up and asks questions that have absolutely f*ck all to do with the gorgeous slide-decks and the pre-prepared answers.

Because buyers don’t buy your deck. They don’t buy your vision. They don’t even buy your business, really.

They buy their future. Their shortcut. Their “I can’t be arsed to build this myself” card.

The question nobody thinks about

I sit down with founders all the time who say: “We want to sell in two or three years.”

Cool. Lovely. Then I ask a question that sounds simple:

Who are you going to sell to… and why will they want to buy you?

And most of them look at me like I’ve just asked them to recite pi backwards while juggling flaming chainsaws.

That happens because so many founders have been fed the same comfortable lie: “Build a great business and the exit will take care of itself.”

Sometimes it does.

Often it doesn’t.

And do you know why? Because “great” and “valuable to a specific buyer” are not the same thing. Mixing them up is a category error that could cost you millions.

Being bought vs being sold

You want to be bought. You absolutely, categorically, with every fibre of your being, do not want to be sold.

Let me paint you two pictures.

Picture one: Someone comes along, looks at what you’ve built, and says: “Oh my goodness, you are so valuable to us. Here is a gazillion pounds. Actually, make it two gazillion. And here’s my watch.”

Picture two: You drag yourself to an adviser on your hands and knees and say: “I’ve had enough of this sh*t. Get me out of here. I’ll take anything from anybody. I’d pay someone to take it off my hands.”

One is life-changing in the champagne-popping, mortgage-obliterating kind of way.

The other ends with you getting stitched up like a kipper, and then spending the earn-out pretending you’re absolutely thrilled about it while dying inside.

So yes, absolutely, build an exit-ready business, but understand that hard and valuable are not the same thing. Not even close.

If you’re going to work your socks off, you may as well point that effort at something a buyer will actually pay for, rather than something that just makes you feel busy and virtuous.

The boring baseline

A buyer can find “growth” anywhere. It’s not special. And they can find “profit” anywhere too.

What they struggle to find is growth plus profit plus a specific strategic reason to exist that isn’t just “because the founder wanted to start a company.”

But you still need the baseline, the absolute bare minimum, the “you must be this tall to ride” of acquisitions:

- At least 10% organic growth (because flat is a slow death, like watching a balloon deflate in real-time)

- At least 20% EBITDA (because “we’ll be profitable later” is how mediocre businesses comfort themselves)

In deal-land, growth is roughly twice as impactful as EBITDA. Not because profit doesn’t matter (it absolutely does) but because growth makes buyers imagine, and imagination is expensive. It’s like the difference between showing someone a seed and showing them a tree. The seed has potential. The tree is just… there.

Right. Now the fun bit. The bit where we get into the actual meat of why anyone would hand you money that could otherwise buy a small island.

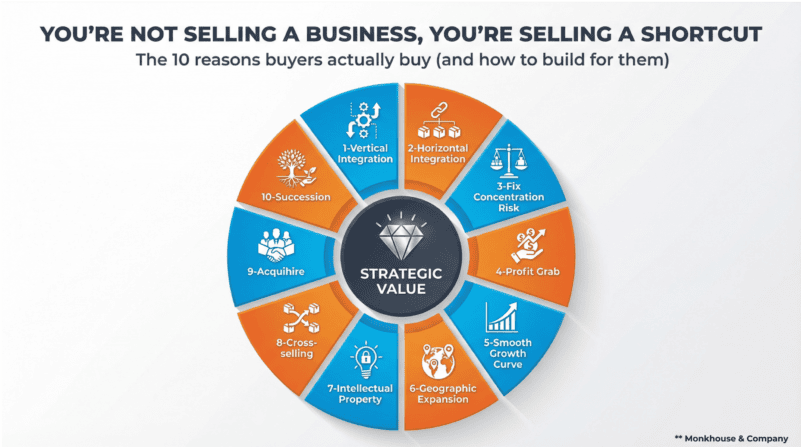

The ten reasons buyers buy

The founder mistake is thinking: “We’re building a business.”

The buyer reality is: “You’re building an asset.”

Which asset are you building? Because if you don’t know, you have no hope of finding the right buyer.

Most acquisitions are driven by at least one of these motivations, and often two or three.

1) Vertical integration

They’re buying a missing piece instead of building it themselves, because building things is hard and time-consuming and they’d rather just write a cheque.

At Peer 1, we built our own data centres.

Why?

- Capture margin (stop paying suppliers to do a chunk of your delivery, like cutting out the middleman who’s been taking a slice for basically existing)

- Control quality (stop being held hostage by third parties who might decide to bollocks things up at the worst possible moment)

If you’re being acquired, you might be someone else’s vertical integration play: they want margin parity, better service quality, or both.

2) Horizontal integration

They want your customers and market share, not your proprietary bullshit or your “secret sauce.”

This is the simplest one to understand, and somehow the easiest one to underestimate, like thinking you can run a marathon because you once walked up a big hill.

At Peer 1 we bought NetBenefit. On paper, it looked like a stupid multiple on EBITDA. The kind of number that makes CFOs spit out their coffee. I think ours actually did.

But we weren’t buying EBITDA. We were buying:

- A revenue stream that looked a lot like ours (predictable, transferable, not held together with string and hope)

- Synergies we could realise by migrating customers out of the third-party infrastructures they were running into ours (those data centres proving their worth again).

That’s how these deals work. The spreadsheet looks absolutely crackers until you factor in the buyer’s post-deal plan, at which point it transforms from “are you having a laugh?” to “oh, that’s actually quite clever.”

3) Fixing concentration risk

Sometimes the buyer isn’t trying to “grow” in some aspirational, vision-board kind of way. They’re trying to stop being one bad quarter away from getting absolutely leathered by the market.

Client concentration is the obvious version: one huge customer, one huge sector, one huge channel partner. Basically, all your eggs in one basket, and that basket is looking a bit dodgy.

But there’s a cousin to this: capability concentration, or being too exposed because you don’t have a credible story in an area the market cares about.

Buyers will pay to remove an uncomfortable weakness faster than they can fix it internally, because internal fixing is slow and painful and involves committee meetings that make you want to claw your eyes out.

4) Profit grab

This is the “we’ll be profitable later” company finally meeting “later”.

If you run a properly profitable business (and I mean actually profitable, not “we could be profitable if we stopped investing in growth” profitable) you’re not “nice to have.” You’re a plug-in profit engine.

And if the buyer needs profit now, you get leverage – because you’re not an optional extra on the menu. You’re the fix. You’re the solution to their problem.

5) Smoothing the growth curve

They need the story to keep working, like a soap opera that can’t just end.

High growth is a great headline. Investors are happy. Champagne all round.

When growth slows, investors get twitchy. Awkward questions are asked. Suddenly everyone’s asking about “efficiency” and “focus.”

So they buy a faster-growing firm to blend the numbers and keep the narrative intact, like mixing premium vodka with Tesco Value stuff and hoping nobody notices.

This is common in PE-backed roll-ups and public companies. Sometimes it’s genuinely smart strategic thinking. Sometimes it’s cosmetic surgery for the P&L. Either way, if your growth rate makes their story better, makes their graph go up and to the right like it’s supposed to, you’re valuable.

6) Geographic expansion

They want a foothold, not a plane ticket and a prayer.

Yes, geography still matters. I know, I know – we’ve got Zoom, we’ve got Slack, we can work across borders easier than ever before.

But buyers still buy local. Credibility is regional. Procurement is weird and parochial. And hiring senior talent is not evenly distributed – that talent tends to migrate towards hotspots relevant to the industry in question.

The key is to own a region – in a real way. Leadership, flagship clients, partnerships, compliance, credibility. Not just ‘we’ve got an office in Barcelona’.

7) Intellectual Property

Founders hear “IP” and immediately think “patents,” because that’s what Silicon Valley told them matters.

Buyers often mean:

- A proprietary method they can sell at scale (process that works, not just theory)

- A platform or dataset that’s hard to replicate quickly

- A license, accreditation, or partner status that takes time and trust to earn

To put yourself into this category, you need to create something genuinely hard to replicate that provides an actual competitive advantage, not just a nice story.

8) Cross-selling

They’ve got customers. You’ve got an extra product/service they can sell into them. One sales team. Two offerings. Instant upsell. It’s a beautiful marriage of convenience.

If you want to be a cross-sell play, you need more than “it would be nice”. You need proof. Rates that speak for themselves. Case studies where actual humans bought actual things. Sales enablement that doesn’t require a PhD. Clear packaging. And an offer that doesn’t require a 90-minute explanation.

9) Acquihire

This is the fast route to senior talent in a tight market, but it’s rarely a gentle journey.

Brands disappear like they never existed. Systems get ripped out. The buyer keeps the talent they want and the rest gets “integrated,” which is corporate speak for “made redundant or so miserable they leave.”

If you suspect you’re an acquihire target, your biggest risk isn’t valuation. It’s deal structure: earn-outs that make you want to fake your own death, retention bonuses that are really just golden handcuffs, and whether you’ll still like your life afterwards or whether you’ll spend three years fantasising about setting fire to things.

10) Succession by acquisition

Sometimes the buyer wants to hand over internally, they’ve got a succession plan sketched out on a napkin, but they’ve got absolutely no one with the entrepreneurial chops to run the next phase.

So they buy a founder-led business and effectively buy a successor and a leadership bench, like acquiring a whole management team without having to do any of the actual recruiting.

Which is exactly the point: buyers don’t buy you for “a nice business” or because you’re “doing well.” They buy you because you solve multiple problems fast.

The 30-minute audit that changes how you run the company

If you’re between 50 and 250 people, you’re already building one of these assets whether you know it or not. The question is whether you’re doing it accidentally or deliberately.

So sit down with your leadership team, ask yourselves the following questions, and start getting deliberate.

1. Pick your top two buyer motivations

Not the sexiest ones that make you sound like a visionary. The truest ones. The ones that make you slightly uncomfortable because they’re so nakedly commercial.

2. Name the actual buyer types

Not “strategic acquirers” or other meaningless crap. Actual names. Competitor? Platform? PE roll-up? US entrant trying to crack Europe? European consolidator? Channel player looking to add depth?

3. Write the buyer’s sentence

“We would pay for them because ______.”

If you can’t finish that sentence crisply, in one go, without umming and ahhing, you don’t have an asset yet. You have potential. Which is lovely, but potential doesn’t buy you a yacht.

4. Decide what to double down on

Next, stop doing the stuff that’s merely hard, and start doing the stuff that’s hard and valuable.

Because the real game isn’t “build a business and hope someone notices.”

Build the specific thing buyers pay multiples for. The thing they dream about in their strategic planning sessions. The thing that solves their problems faster than they can solve them internally.

And if you get that right, you don’t need to beg to be sold. You don’t need to hire some overpriced adviser to pimp you out.

You get bought.

The “f*ck me, here’s a gazillion pounds” kind of deal.

Not the “f*ck me, please just make this stop” kind of deal.

Know the difference. Build for the difference. And may your exit be the kind that requires champagne, not therapy.

Written by business coach and leadership coaching expert Dominic Monkhouse. You can order your free copy of his new book, Mind Your F**king Business here.